|

|

Links to Palm Beach County's Department of Environmental Resources Management pages about Sea Turtles:

Light Pollution Hurts Reptiles in the Environment

This page covers:

- Understanding, assessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches.

- Behavior of Loggerhead Sea Turtles on an Urban Beach. I. Correlates of Nest Placement

- Behavior of Loggerhead Sea Turtles on an Urban Beach. II. Hatchling Orientation

- Do Embedded Roadway Lights Protect Sea Turtles?

- Shots from the Front on the Beach

- Sea Turtles Have Color Vision!

Light pollution's impact on other species in the environment are found here.

Reptiles

Of the oldest reptile groups, the earliest known turtles date from 215 million years ago, making them a more ancient group than lizards, snakes and crocodiles. In my opinion, when you look at one, you can almost sense their history on this planet. Their motions feel ancient and some even become ancient by living standards as they can live much longer than humans. They naturally seem to convey a mellow wisdom that hard to find anywhere else in the animal kingdom. So with the understanding of their successful survival on this planet, it may come as a shock to learn of their endangerment by a reckless, so full of an arrogant intellegence, youngsters to this planet: us. Whether by improperly geared bottom trawler fisher nets (those without large "turtle excluder devices" or "TED"s built into them), buildings that encroach to their traditional nesting locations, irresponsibly tossed trash that chokes a hungry turtle, discarded monofilament fishing lines that loop, twist, knot and strangle a passing sea turtle, or by our ever growing artifical lights that confuse and mislead hatchling sea turtles away from their ocean dwelling lives, our actions have threatened to eliminate them in ways that the dinosaur killing asteroid, 66 million years ago, never could do.

As far as I've learned, in the reptile family, turtles are affected by light pollution more than any other, though I may have to investigate into snakes, as well. Sea turtles, particularly, continue to be seriously affected by light pollution. They are not only affected by the radiant pollution during times of nesting, but also when they emerge as hatchings. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Fisheries Service is a federal agency that is responsible for the stewardship of the nation's living marine resources and their habitat. In their Recovery Plans for Endangered and Threatened Species, they have identified and measured the various threats to the sea turtles populations, such as the Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta). For the Loggerheads and other sea turtles, the exponentially growing light pollution is one of the most serious threats to their existence.

Why should we care if the turtles are negatively affected by the lights? Well, not only should we be morally concerned that our lights are impacting fellow species of this planet, but also, in a more economic sense, if Florida wants its beaches to be as tourist and visitor friendly as possible, then having something out there to help control deadly man-of-war jellyfish is one thing that they would want around. Jellyfish are one of sea turtles' favorite things to eat. Sea turtles have spines in their throats that ensure that once swallowed, a jellyfish has little chance of being rejected. Which is also why floating trash, such as plastic bags or used helium balloons, is so deadly to them, they can't regurgitate it out. Thus, sea turtles are also good for Florida's tourism and ultimately, its economy.

Understanding, assessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches.

Source: Florida Marine Research Institute Technical Report TR-2. 73 pages, 1996.

Witherington, B. E.1, and R. E. Martin2.

1Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Marine Research Institute, Tequesta

2Ecological Associates, Inc, Jensen Beach, Florida

During the nesting season, female sea turtles such as the endangered Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) prefer to nest on very dark beaches, if they can find it. And on the urban beaches of Boca Raton's, they find it in a rather surprising place: near the beach condominiums. Here's why:

Behavior of Loggerhead Sea Turtles on an Urban Beach. I. Correlates of Nest Placement

Source: Journal of Herpetology, Dec 1995, Vol. 29, No. 4, p560-568.

Michael Salmon, Raymond Reiners, Craig Lavin, and Jeanette Wyneken

Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida.

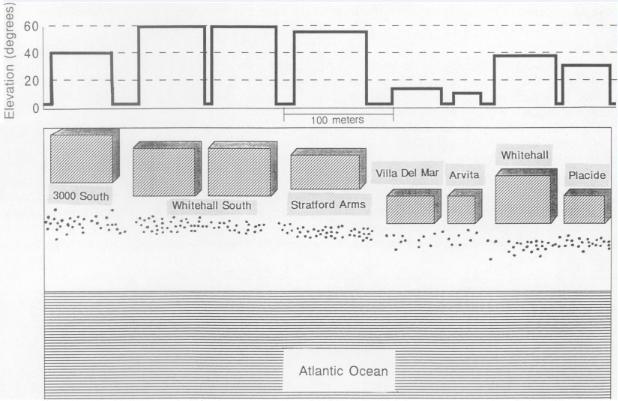

The researchers looked for the physical variables of

where sea turtles dug their nests on a city beach. For the four year period, the nesting patterns on the beach were statistically

identical. They found that the nestings were densely concentrated near tall objects, such as clusters of mature Australian pine

trees or immediately by multi-storied condominiums, located between the beach and the city. The density variation did not depend

on the offshore depth profiles or the beach width. Female sea turtles do not nest-cluster like this in front of tall objects

(dune or vegetation) at natural rookeries. Their two part graph shows the elevation of the buildings in the "condominium row" in

Boca Raton in the top part and mapping of the buildings and the location of the turtle nests in the beaches. The nesting

concentrations increased with the elevation of the building.

The researchers looked for the physical variables of

where sea turtles dug their nests on a city beach. For the four year period, the nesting patterns on the beach were statistically

identical. They found that the nestings were densely concentrated near tall objects, such as clusters of mature Australian pine

trees or immediately by multi-storied condominiums, located between the beach and the city. The density variation did not depend

on the offshore depth profiles or the beach width. Female sea turtles do not nest-cluster like this in front of tall objects

(dune or vegetation) at natural rookeries. Their two part graph shows the elevation of the buildings in the "condominium row" in

Boca Raton in the top part and mapping of the buildings and the location of the turtle nests in the beaches. The nesting

concentrations increased with the elevation of the building.

The researchers believe that the turtles are using tall objects as shields from the artificial lighting from the interior land. The taller and more complete the object, the higher the nesting density. Planting vegetation, trees and establishing dunes on urban beaches may be effective methods for attracting nesting turtles to these sites, though their densities were not as high as the typically summer vacated condos. One representative turtle from such a condominium shielded nest was Milton of the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center here in Boca Raton.

The Boca Raton beaches were found to be ideal for the study because,

- the city protects all nests and maps their locations

- they had access to data for four consecutive nesting seasons, which allowed them to determine if females consistently preferred some nesting sites over others

- nesting densities at Boca Raton are relatively high for an urban beach, which decreases the probabilities of chance in the nesting locations

- the beach is divided into long regions backed by heavily vegetated public parks or by on-the-beach condominiums. This allowed them to compare how females responded to each area.

The turtles find the beaches to be ideal because of their proximity to the ocean currents and they used to be dark.

So for all the inland folks complaining about the unfair bail out burden due to expenses that folks living on

the coast endure during hurricane storms, here is one case where the inland folks owe the coastal condominium residents a debt of

gratitude. Dr. Salmon was quoted saying about this fact that the problem is fast becoming not the amount of light at the

beach but rather sky glow from inland.

But understand this clearly, this nest-clustering

is a dangerous situation for the sea turtles.

Dr. Salmon points out that as the density increases, sea turtles will at some point start to dig out older eggs in order to deposit

new ones, and in doing so, she will kill the older eggs. (Such actions already occur for the critically endangered Kemp's Ridley

turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) during their "arribadas" or arrivals to mass nest at Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico.) In addition

to nesting excavations, these urban nesting sea turtles are literally now are "putting all their eggs in one basket/beach". One

hurricane, one oil slick accident or one predator could put a serious dent into the population levels, not to mention the increased

risk due to deadly microbial blooms in the sands from the left over dead eggs. (Biologist, 2003, Vol. 50, No. 4, p163-8).

Behavior of Loggerhead Sea Turtles on an Urban Beach. II. Hatchling Orientation

Source: Journal of Herpetology, Dec 1995, Vol. 29, No. 4, pages 568-576

Michael Salmon, Melissa G. Tolbert, Danielle P. Painter, Matthew Goff and Raymond Reiners

Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida.

Once the baby turtles hatch from their shells, they dig their way almost to the surface to wait for the cooler night to fall. When it does, then they make a break for the sea. However, finding the sea is the hatchlings' first challenge. Remember, these little tykes can hardly raise their heads above a couple of centimeters (not even an inch). Bumps or footprint depressions in the sand may be enough to prevent the turtles from even seeing the sea, hence they have to rely on indirect cues. They quickly scan around and crawl instinctively away from the darker locations, which would normally be made by the inland vegetation and dunes, toward the lower, flatter and brighter locations, which typically is directly to the sea, ±20 degrees. However, coastal lights interfere with sea-turtle hatchlings. Artificial lights, both from nearby or from distant sky glow, can confuse the hatchlings and cause them to crawl onto roads or into communities, often leading to fatal exhaustion, dehydration, predation or even being crushed by cars.

The authors conducted field

experiments to study the emergence behaviors of hatchling sea turtles in various lighting conditions. They did this by plotting

the tracks the hatchlings made as they crawled. The experiments were conducted as follows. Boxes with hatchlings were taken to

the beach after dark. The boxes were opened on location to expose the turtles to ambient light and cooler evening temperatures

which induced crawling activity. Turtles were placed, either singly or in pairs, in a shallow (1-3 cm deep) pit located in the

center of a 4 m diameter circle (which are called

The authors conducted field

experiments to study the emergence behaviors of hatchling sea turtles in various lighting conditions. They did this by plotting

the tracks the hatchlings made as they crawled. The experiments were conducted as follows. Boxes with hatchlings were taken to

the beach after dark. The boxes were opened on location to expose the turtles to ambient light and cooler evening temperatures

which induced crawling activity. Turtles were placed, either singly or in pairs, in a shallow (1-3 cm deep) pit located in the

center of a 4 m diameter circle (which are called beach arenas

) drawn on a smoothed, leveled sand surface. Most turtles

immediately left the pit and began crawling toward the periphery. As each turtle crossed the arena boundary, it was captured and

released. The tracks hatchlings left in the sand were traced. A few (<5%) of the turtles failed to exit the pit within 2 min

and were excluded from the analysis.

The images show a set of plot of hatchling tracks. In one experiment, lights were temporarily turned on for portions of the night. Red Reef park has large Australian pine trees to its west which block inland lights from hitting its beaches. So when a pavilion light at the park is turned on, hatchlings crawled westward toward the light and away from the ocean to the east. But after the light is switched off, they crawled east. At another part of the beach, an apartment light at the Stratford Arms and a garage light from an adjacent building seriously disrupted the hatchlings' sea finding. However, after the apartment light is extinguished, most turtles crawl toward the sea.

Hatchlings are attracted to lights and crawl inland, or crawl aimlessly down the beach, sometimes until dawn, when terrestrial predators or birds get them.

- Dr. Michael Salmon.

In Palm Beach county, beach lighting ordinances exist to eliminate artifical light from illuminating the beaches during sea turtle nesting season, which runs from March 1st to October 31st. In 1986, the City of Boca Raton was one of the first municipalities in the County to enact such lighting ordinances. Artificial lights on the beaches attract sea turtle hatchlings away from the ocean and inwards to the land, where they either die from exhaustion due to not finding food and water, being eaten by predators, crushed by cars or killed in other unnatural obstacles such as in sewer drains.

We are still not certain how they do it, but sea turtles are amazingly and innately phylogeographic to their natal beaches. It takes about twenty-five years for a hatchling from our beaches to complete the Northern Atlantic Ocean current circuit and return as an adult to lay her eggs on our beaches. (Just imagine a twenty-five year old human returning to their birthplace without directions, a road map or even a simple description of the place!) In that 25 year time, however, the light pollution from the interior land, growing exponentially at 6% per year, will be 4 to 5 times brighter than what the turtle experienced as a hatchling. Because nesting females do have a high site fidelity for laying their eggs for the next generation, their species has a low gene flow rate. The TEWG states:

"Should an assemblage be extirpated, regional dispersal will not be sufficient to replenish the depleted nesting assemblage within thousands of years."

- Turtle Expert Working Group

2000 Assessment Update for the Kemp's Ridley and Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations in Western North Atlantic.

U.S. Dept. of Commerce.

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-444

Do Embedded Roadway Lights Protect Sea Turtles?

Source: Journal of Environmental Management. Sept. 2005, Vol. 36, No. 5, pages 702-710.

Lesley Bertolotti1 and Michael Salmon2.

1Broward County Department of Planning and Environmental Protection, Biological Resources Division,

Fort Lauderdale, Florida

2Department of Biological Sciences, Florida

Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida.

Roadway Lighting and Hatchling Orientation

The researchers found the following:

1.) Turtle orientation varied with the influence of background lighting levels. During a full Moon, the contrast between artificial lights and the background was at their lowest, thus neither the streetlights nor the embedded lights affected hatchling orientation at their sites. However, during a new Moon when contrast was greater, lighting disrupted turtle orientation. It has been historically found that the visually based orientations of turtles, birds and other wildlife are also disrupted more often by artificial lights during a new Moon than during a full Moon. In another recent study, background light levels were changed under laboratory conditions. Here, too, it was found that luminaires disrupted hatchling orientation when background lighting was low, but not so much when the background lighting was high.

2.) It has been found that direct exposure to street lighting disrupts hatchling orientation. The spectral output of high pressure sodium (HPS) lights contains relatively short wavelengths, including those between 470 and 530 nm that strongly attract the turtles. When these wavelengths are excluded by light filters, attraction to the remaining longer wavelengths declined. Thus, HPS luminaires have the potential to disrupt hatchling orientation if their light is visible at nest sites. They found that this disruption occurred when the turtles were exposed to the street treatment.

3.) Embedded roadway lights at our sites could not be detected at the beach.

They observed almost no difference in light scatter between the all-off and the embedded light treatments. In contrast, overhead

street lighting resulted in an obvious increase in illumination.

3.) Embedded roadway lights at our sites could not be detected at the beach.

They observed almost no difference in light scatter between the all-off and the embedded light treatments. In contrast, overhead

street lighting resulted in an obvious increase in illumination.

Image credit: M. Salmon.

4.) Under typical weather conditions (clear or scattered cloud cover), embedded lighting had no statistical

effect on turtle orientation. This conclusion was based on their measurements which suggested that embedded lighting did not reach

the beach and when a replicate assay done at the same site under more typical conditions, hatchling orientations was found to be

accurate to the sea. As to be expected, hatchlings exposed to both embedded lighting and overcast conditions were the exception.

But this difference is understood to be attributed to sky glow

(light scattered to the beach by mist and clouds over densely

lighted areas from more distant locations). Unfortunately for the research, overcast conditions did not occur on evenings when all

lighting was turned off. Tests done under those conditions might have provided added evidence that sky glow could, alone, compromise

turtle orientation.

At the study's sites, lighting from coastal development originated from the West (the interior land including the city of Boca Raton), from the South (Hillsborough Beach), and from the North (Highland Beach). Under clear or partly cloudy skies, that lighting can be partially (from the N and S) or completely (Boca Raton) excluded by the foliage at the Spanish River Park testing site. However, this barrier failed when extraneous lighting was reflected down to the beach from clouds overhead. While enforcement of lighting ordinances has eliminated direct exposure to many luminaires on the beaches, similar problems are increasing at many nesting beaches in Florida. The primary cause of hatchling seafinding disruptions in Southeast Florida is now indirect lighting (sky glow) and from adjacent developments.

Limitations of Embedded Lighting

Generally, any light visible at the beach can potentially affect hatchling orientation and there are strategies that can be followed for correcting the disruptions. One strategy is to use new technologies when they become available, followed by beach arena tests to verify their efficacy. LEDs are not new, for they are used in tunnels, pedestrian crosswalks, and at airports to illuminate runways, their use as a management tool to reduce lighting problems for wildlife is a unique, and unanticipated, application.

The researchers found that embedded lighting darkened the beach at their study site, however, their use may

not be appropriate at other coastal locations. Embedded lighting is most beneficial where other problem lights are identified and

can be managed. At Spanish River Park, the streetlights were suspected to be the primary, though probably not the only, cause of

orientation disruption (skyglow was believed to be another cause; K. Rusenko, personal communication). Given that knowledge,

turning off the streetlights and substituting in their place an embedded lighting system succeeded as a management strategy.

However, embedded lighting might not be beneficial at sites where the lighting environment is more complex

, such as those

with many luminaires and/or some being well inland, and where these sources are difficult to manage.

The benefits of embedded lighting will also be reduced if light scatter from adjacent coastal communities is not controlled. For example, an elaborate and thorough lighting plan was implemented at the Patrick Air Force Base near Cape Canaveral, Florida. The result was a darkened base complex and nesting beach on its eastern border. Initially, these changes resulted in a significant decline in hatchling orientation problems. However, problems are now increasing again at each end of the base because the beach is exposed to light from neighboring communities (D. George, personal communication). A similar scenario might develop at Spanish River Park if no steps are taken to manage lighting at Hillsboro Beach and Highland Beach. Comprehensive planning is therefore essential for long-term solutions to lighting problems.

Finally, embedded lighting on a coastal roadway affects the organisms that use the nesting beach (turtles), as well as those using the roadway and the park (humans). Its use must therefore be evaluated from the perspective of both organisms. In a companion study to ours, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) sponsored a project to determine the psychological response to, and safety record of, embedded lighting from the perspective of motorists, pedestrians, and bicyclists. The results were positive (Ellis and Washburn 2003). Thus, at our study site, embedded lighting appears beneficial both to turtles and to people.

Shots from the Front on the Beach

So how bad is it really? What does it look like from the hatchling turtles' point of view? Well here is a

small collection of images that show what the beaches of Palm Beach County look like in the dark

, which of course, they are

not. As Dr. Salmon pointed out in his paper above, a great deal of the light comes NOT from sources directly on the beach, but

from lights coming from the interior land. If you have questions as to what is permissilble for lights at the beaches, you can

consult a list of lighting ordinances for different

communities of Florida have been compiled by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Also, if you want to become more active in this effort, then consider the Sea Turtle Oversight Protection organization or SeaTurtleOP.org. These folks are on the front lines of this effort every night. Not just working to help the hatchling turtles get to the sea, but also to end this problem once and for all.

| The first two images are of South Beach Park in Boca Raton. As the pictures indicate, they were taken on April 22nd and May 13th, 2010. The atmosphere refracts some of the light from the nearby and distant towns to the south, such as those in Hillsborough Beach, in Broward County and possibly Ft. Lauderdale, creating the awful airglow. The conditions are made worse by the clouds as seen in the May shot. Let your mouse cursor hover over the picture to see how bright the clouds are during the night. The clouds reflect the light to visibly illuminate the beaches of Boca Raton, for light just does not stop at a fence or at a border. Boca Raton tries to keep its beaches dark for the sea turtles' benefit. But as the towns down here are so close together, then lights from nearby towns can interfere with Boca's noble efforts. |

|

|

| These images look to the southwest where taken at Spanish River Park in Boca Raton, FL. Photographs by Dr. Kirt Rusenko. |

These images are taken in Spanish River Park in Boca Raton on April 22nd and May 13th, 2010. Once again,

the air refracts the light from the distant towns to the south creating the airglow seen in the shot. Clouds worsen the conditions

by providing a surface to reflect the light of off and cast it about everywhere, which can be seen when you let your mouse cursor

hover over the picture to see the cloudy night's light.

Just in case the folks down here have forgotten, nighttime clouds are

not supposed to be bright white, but appear as dark masses blocking our views of the starry sky. The fact that they are bright is

due to the artificial illumination from people below. Not only does this directly affect the turtles, but it also has an impact on

almost every living thing from protezoa to humans, for we nearly all biologically use light as an indicator of time so it also has

an impact on our health. It also has an impact on

our security, our culture and our wallets.

Of course, all of this is not to say that the beaches themselves are perfectly dark. There are still sources of light

on the beaches that can fatally disorient sea turtles.

This photograph is of Deerfield Beach's Pier being lit at night

and was taken by Dr. Kirt Rusenko.

He has observed that hatchling sea turtles will tend to swim towards such a lighted pier

only to be eaten by their predators. Such observations have convinced him that ideas for placing floating illuminated

bouys in the water as a way to attract sea turtles away from land and out to sea are unsound. Here, too, the hatchlings would

become stuck there and congregate around such bouys, to be easily picked off by predators, and accelerating their deaths.

Here is an image of a mother sea turtle making her way

back to the ocean after depositing her eggs in a pit that she has dug in the sand. This ancient act, that goes back to a time of

the dinosaurs, is what enables these air breathing creatures to live and reproduce.

This photo was taken just north of

tower 6 in South Beach Park on May 26th, 2010 by Dr. Kirt Rusenko.

Down in Fort Lauderdale, FL, the lighting does not seem to be controlled at all. While it has an ordinance to mandate the beaches to be dark, it is rarely enforced.

It is the policy of the City of Fort Lauderdale that no artificial light shall illuminate any area of the incorporated beaches of Fort Lauderdale, Florida.-- Ft. Lauderdale Lighting Ordinance Sec. 6-51

What is shown here is a video of the lighting conditions taken on the beach there and how the turtle move right

towards it. The city's apathy is just infuriating. The Points

of America

building in the city has its own continued set of abuses and violations that simply defy reason.

The nearby town of Hollywood has just enacted an ordinance that requires lights to be dimmed, replaced, hooded or retrofitted by 2015 along the beach, including its historic Broadwalk commercial district. This change occured only because they were forced to do it if they expected to receive permits to widen the severely eroded southern end of its beach. The five year retrofitting period seems very slow. Richard WhiteCloud, a Fort Lauderdale conservationist who leads a group that rescues wayward sea turtle hatchlings, calls the five-year implementation deadline as a "joke." He has said that the city would have accomplished the job by now if it hadn't fought the requirement for so long. The two problems I see from this is 1.) if they decide to give up on the plans to expand the beach, then they wouldn't have to work on their problematic lights and 2.) what is the guarantee of enforcement?

Finally we have an image that is a compressed version of view from the Blue Heron Blvd bridge in Riveria, FL. Clicking on the image opens the original .pdf. The photographer was Christina Mendenhall taken at the top of the Blue Heron Bridge.

The panoramic picture from the Blue Heron Bridge and of the Palm Beach Inlet is an interesting perspective

because our jurisdiction for the sea turtle lighting ordinance is only in effect 600 feet west of the mean high water line. From the

bridge, you can see how much darker the coast is compared to interior land. In fact, the lights from the interior land seem to end as

if it hit a wall up and down the Intercoastal waterway. Of course that is only how it appears from this angle. The lights can be seen

quite a way out from the main land. This coast of Florida is quite parallel to lines of longitude; there is a distinct interior

lighted region to the west and a darker oceanic region to the east. As light radiates in all directions, it is very apparent for the

interior land lights to emanate outwards to the sea. So unless it is cloudy, it is unlikely that light rays heading eastwards will

bend to the north. Hence, the illusion of the wall

.

Light from the interior lands does reach our beaches and disrupts the sea turtles trying to nest on the beach and those hatchlings that emerge from the nests. It is up to all of us, not just those living on the coast, to cease being such a detriment to our fellow species of the planet, to help them survive our debilitating apathy of years past and to encourage and celebrate their positive growth from here on.

Sea Turtles Have Color Vision!

Prof. Mike Salmon, Department of Biology Sciences, Florida Atlantic University

We know that marine turtles have good eyesight and use it to hunt for food and to detect and avoid their predators. That leads to an obvious question: Do marine turtles see and use colors to identify objects, or is their visual world one of different shades of grey, like a black and white movie? And, how do you get the turtles to answer these questions?

| Morgan Young, a Masters degree student in Biology at Florida Atlantic University, won an Archie Carr Best

Student Poster Award at the Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation, held on April 2011 in San Diego, California.

Her research on marine turtle color vision was supported by The National Save the Sea Turtle Foundation. Her co-authors were Prof.

Richard Forward (Duke University), and expert on vision and biological rhythms in marine animals, and her behavioral biologist

advisor at FAU Prof. Mike Salmon. Here she is at her poster while it was on display at the Symposium. Students were quizzed by several judges who determined which projects should receive awards. |

|

Morgan used a two-stage process to obtain the answers. The first state, done with hatchlings, took advantage of an innate response used by the turtles to locate the sea from the nest; they crawl toward a brighter area using a response known as a phototaxis. Morgan used hundreds of hatchlings to determine the dimmest blue, green and yellow lights that attracted the hatchlings to each color. That enabled her to determine with certainty that the turtles could see each light, but not whether they saw each light as a color or as a shade of grey.

| Apparatus used to train older turtles to make light discriminations, in this instance between a green

light (left) and a blue light (right). During training, the turtle is first confined to the start area, as shown to the right.

When the clear barrier between the start area and arms is raised, the turtle swims down one or the other arm but receives a shrimp

reward only if it selects (in this case) the arm with the blue light. Once trained, it will swim toward the blue light, regardless

of where it is located (left or right arm) or its brightness relative to the green light. This turtle is already trained to blue

as it is trying to swim toward that arm, even before the clear barrier is raised. The second state required training older turtles to swim toward one of a pair of colored lights, both brighter than the ones used to induce a hatchling phototaxis. To complete this phase, she had to train the turtles to associate one color with food reward (a piece of raw shrimp) and ignore the other (unrewarded) color. Over several weeks, she managed to train one turtle to distinguish between a blue and green, a second between a green and yellow, and a third turtle between a yellow and blue light. But that result still left unresolved how the turtles made the discrimination. Was it by seeing a spectrum of different colors or by seeing a spectrum of brightness on a white through grey to black scale? |

|

In the final set of experiments, Morgan ran many trials with each trained turtle while varying the brightness of the pairs of colored lights relative to one another during each trial.

If the turtles always swam toward the brighter (or dimmer) light, regardless of its color, then the turtles were color-blind. However, if the turtles always swam toward the same colored light, regardless of its brightness, then the turtles had color vision. All three turtles consistently chose the right color no matter what its brightness in a very convincing demonstration of color vision.

Florida Atlantic University

Boca Raton, Florida

E-mail: vandernoot at sci dot fau dot edu

Phone: 561 297 STAR (7827)